Mom

by Mike Thompson, 4/18/2020

It's been well over a decade since Mom died, but I'm still having a hard time starting her biography because I still don't think I've got the words to do her memory justice. She was a truly remarkable woman, and by far the biggest influence in my life. She was full of faith, courage, energy, and determination. She radiated love every single second, even when delivering the tough love that I sometimes needed as a youngster.

Agnes McFadden was born in 1918 on a farm in North Dakota. She was the fifth of seven children: Rosemary, Andy, Elizabeth, Helen, Mom, Hugh, and Edith (AKA Honey). Her father, Andrew McFadden, and her mother, Ellen Barret, had both staked out 40 acres of Homestead Act land, which they farmed together after their marriage. They took part in the last stage of America's great westward migration, which was powered by the immigrants' dream of owning their own land. Mom often talked about growing up on the farm, and her childhood was amazingly different from mine.

In the 1920's and 30's, farm machinery was still pulled through the fields by teams of horses, as small farmers didn't yet have enough money to afford gas-powered tractors. Mom often talked about harnessing the horses in the barn in the morning. She rode a horse to and from the one-room schoolhouse where she attended elementary school. At home, hot water was heated in a reservoir in the wood stove, which also served for cooking. If you wanted a bath you filled up the reservoir with water, started a fire, then carried the hot water from the stove to the tub to fill it up before you got in. In the winter they tied a string between the door of the house and the outhouse, so that you could find your way out and back in a snowstorm. Given the way of life in rural North Dakota in those days, Mom grew up in the 19th century as much as she did the 20th century.

In the early 1930's, with the Great Depression gripping the economy, drought struck the Midwest. These were the Dust Bowl years. Mom talked about her dad planting wheat only to see it sprout, wither, and die in the sun, with no rain to provide moisture. She talked about the cows having to eat thistles because they were the only plant that would grow during the drought.

By the mid-30's they were really struggling. Older brother Andy and older sisters Rosemary and Elizabeth had left to find jobs elsewhere. With the older son gone, Mom took a year off from high school to help her dad with the farming. She said that when she finally went back to finish high school she always wore long sleeves, in order to hide the muscles she had acquired from the hard, physical labor she had done.

I remember asking Mom what she used to do for fun when she was a kid. She replied, "We sat down." So true of that generation, who measured their worth by their work. When I was growing up, describing someone as "hard-working" was the considered to be best thing you could say in their favor.

With television still decades from being invented and radio programs and movies still pretty new, entertainment was something that you provided for yourself using your own imagination and skill: singing, playing cards, dancing, or playing the piano (which so many homes had in those days). I remember Mom singing "Oh what a beautiful morning!" (from the musical Oklahoma) as she fixed breakfast. Our next-door neighbor, Gabe Fischer, often whistled while he worked, as did other men. They were a generation that knew how to have fun, cheer themselves up, and enjoy one-another's company.

Common in Mom's generation's language were references to the other living things they shared their world with: plants, animals, and insects. They grew up spending most of their time outdoors, especially those who, like Mom, grew up on small farms. They were intimate with the physical world in a way that's rare today. Many of the expressions that they used, and which I heard while I was growing up, are no longer heard in today's English. They lived in the world before television - before we became separated from the objects of our attention and imagination by a pane of glass.

- Horsefeathers! [Rubbish! Baloney!]

- Like a bull in a china shop. [Behaving in a rough and inconsiderate manner.]

- Cuter than a bug's ear. [Something small and adorable, like a young child.]

- Not enough water to drown a spider. [A very small amount of water.]

- Running around like a chicken with its head cut off. [In a state of agitated confusion.]

- Beating a dead horse. [Belaboring a point.]

- Taking the bull by the horns. [Confronting a difficult issue head-on.]

- Knee-high to a grasshopper. [Very short, like a small child.]

- He has a bee in his bonnet. [He has some issue on his mind that he's adamant about.]

- Smaller than a gnat's eyebrow. [Very, very small.]

- Snug as a bug in a rug. [Warm, cozy, and comfortable.]

- A fly in the ointment. [A small problem that spoils the whole plan.]

In 1936 her dad, Andrew had to admit defeat, as did so many other small farmers from North Dakota down to Oklahoma. An auction was held to sell what they could, neighbors gathering to buy whatever they could afford in order to provide a little money for the journey that was ahead of the McFaddens. Then they fit what they could in the Model A and headed west, over the Rockies and to Yakima, Washington. Yakima was known as "Fruit Bowl of the Nation", with cherry, apricot, peach, pear, and apple harvests spanning the summer and fall months. There they found work in the fields and the canneries.

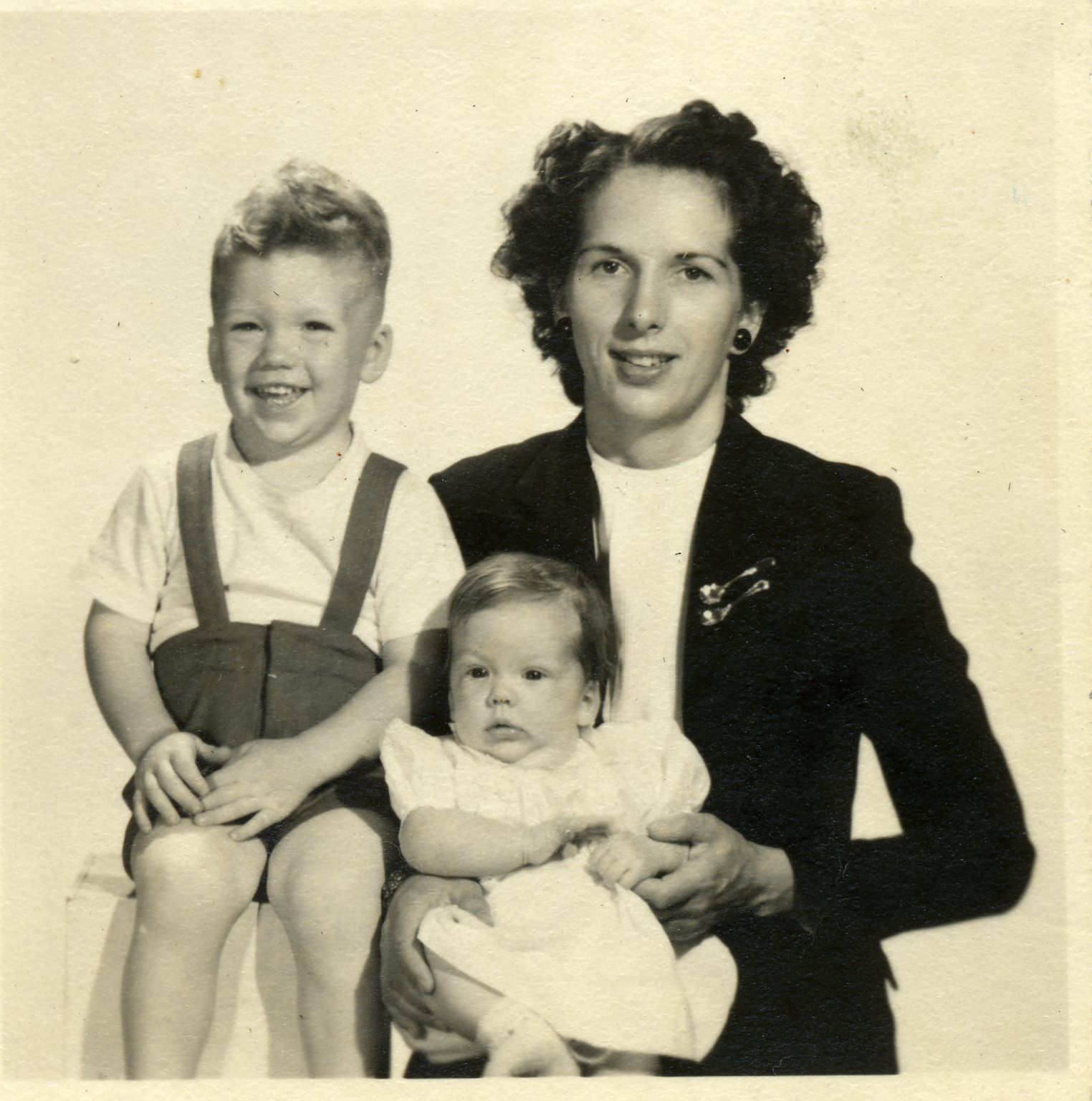

Agnes McFadden and Albert "Tommy" Thompson, my dad, met and were married shortly before the start of World War II. During the war, while he was flying in the China/India/Burma Theater, their first child, Bobby was born. Two years later my sister, Susan was born. They spent time in Yakima, Boise (where Dad grew up), and Lima, Peru, where Dad flew a float plane into the upper Amazon for Standard Oil.

In 1954, the year I was born, Dad and Mom bought a house in Yakima at 1409 South 12th Avenue, about two miles north of the airport. That's where we lived most of the years while I was growing up, except the years in the late 1950's and early 1960's when Dad was flying for Wien Airlines and we lived in Nome or Fairbanks, Alaska.

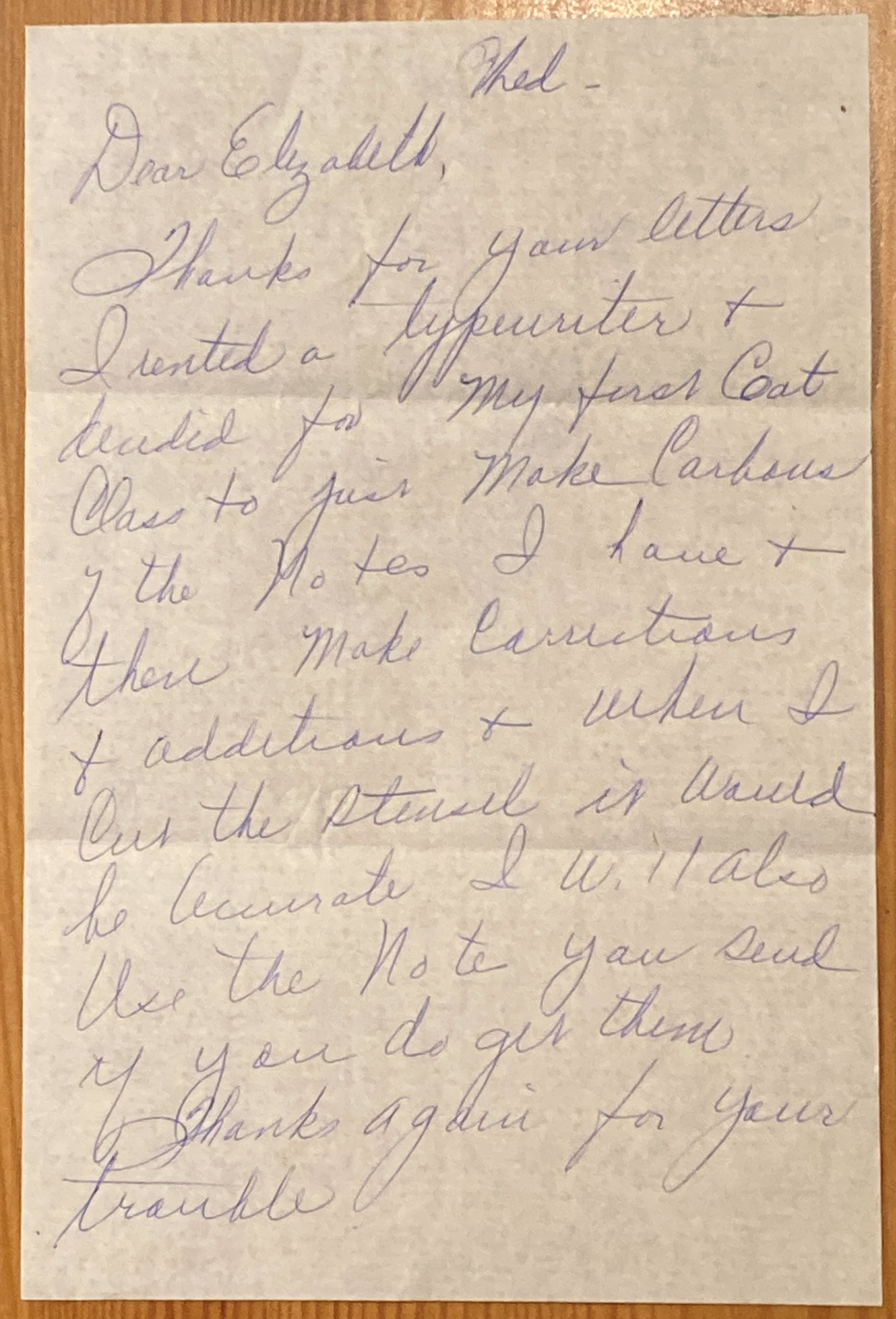

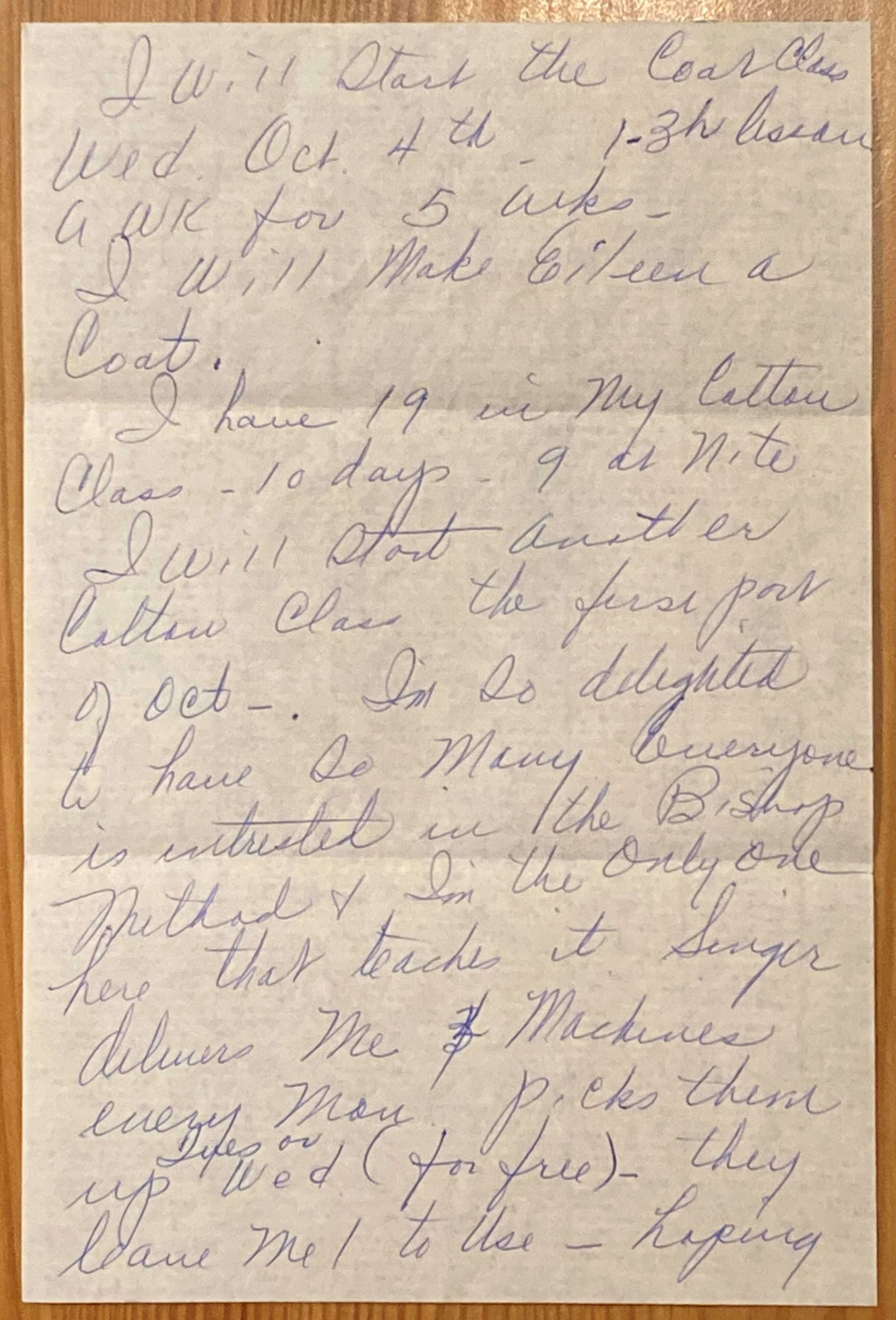

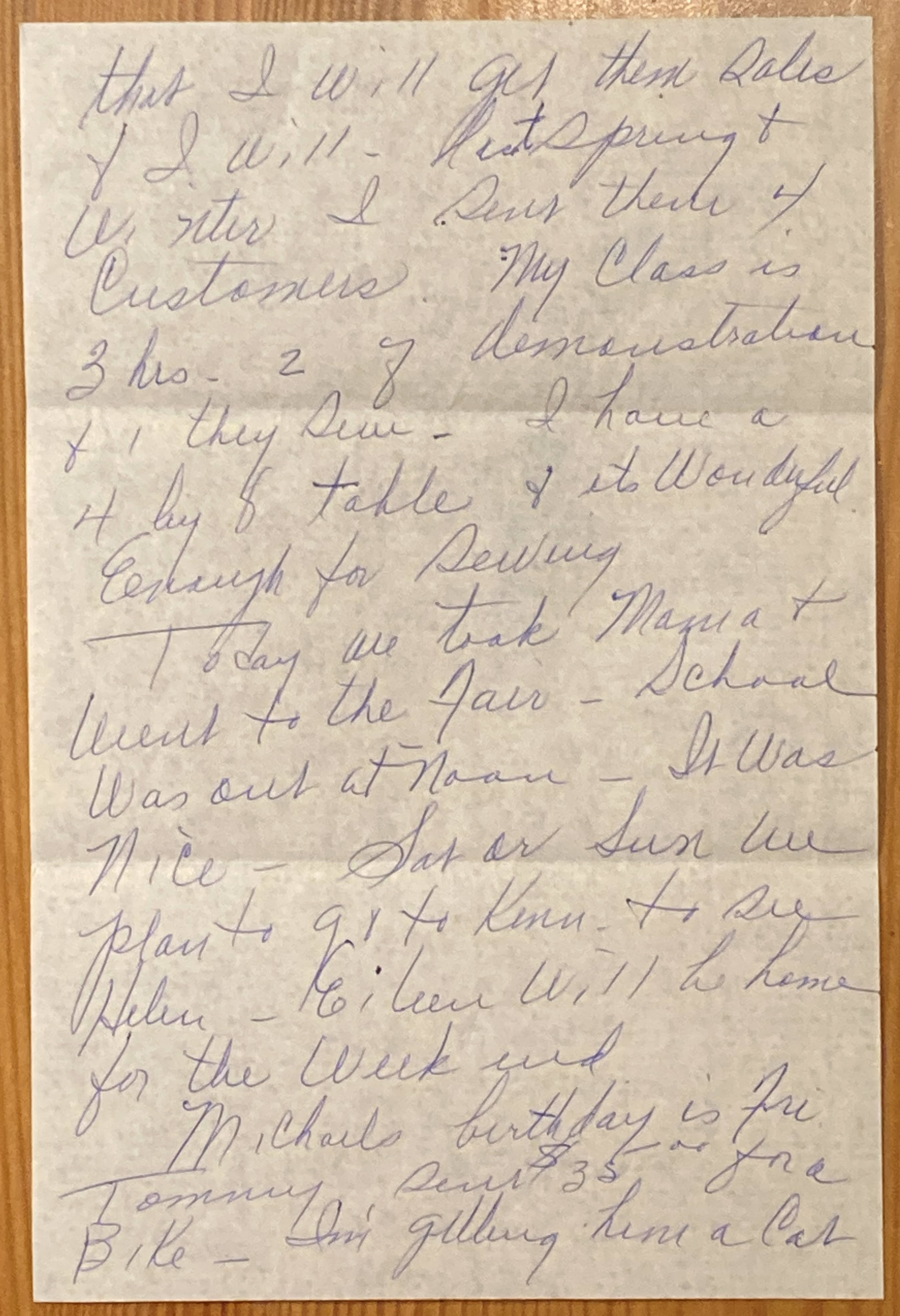

Mom's sister, Elizabeth (McFadden) MacMillan, hung on to many of the letters she received, and shortly before she died she gave a number of them to my sister, Susan. The letter below was written by Mom in September of 1961 in her beautiful cursive hand. In it, Mom talks about her preparations for the sewing classes that she was teaching in our home at 1409 South 12th Avenue in Yakima: what she's teaching, how many students are enrolled, how she'll make copies of her teaching materials, the sewing machines she's being loaned by the local Singer Sewing Machine representative, and so on. Her letters during these years are almost always a lot about sewing.

Early September was the time for the Central Washington State Fair, held at the Yakima Fairgrounds, which we attended most every year. Mom mentions an upcoming trip to Kennewick to visit her sister, Helen. My birthday is approaching and Dad has sent down $35 to buy me a bike. I still remember the one she bought, a red JC Higgins that I rode to and from Hoover Elementary School and around the neighborhood.

Mom closes by talking about how nice the weather is in Yakima, as opposed to Alaska, where we had been living and where I had attended Kindergarten. Her "What a treat after being in Fairbanks. Life seems worth living here." is telling. Years spent far from her parents, brothers, and sisters, facing sub-zero temperatures while waiting to see if Dad would make it back alive from his latest flight into the Alaska bush, had taken a toll.

In January of 1963 I was in 3rd Grade at Hoover Elementary School in Yakima. I remember my teacher, Mrs. Hay calling me up to her desk to tell me that Myrtle Weber, a neighbor, was coming to pick me up and take me home. I asked why, but she wouldn't say. When I got home Mom told me that Dad had died in a plane crash at Barter Island in Alaska. Bobby was living in Fairbanks at the time, having just finished high school and started at the University of Alaska, and was working for Wien as a baggage handler. Susan was living in Yakima with Mom and I while finishing high school at Saint Joseph Academy.

Suddenly, Mom had to carry the whole load herself. I remember her tucking me into bed at night before she left to work graveyard shift at the cannery. Later, after she had taught herself to sew and was doing alterations and teaching sewing lessons in our home, I remember waking up before school, walking out past the kitchen into the sewing room, and finding Mom with her head propped on the sewing machine, where she had fallen asleep in the wee hours while working. She would wake when I walked into the room, raise her head, wish me good morning, and start sewing again.

In the spring of 1968 I was in 8th Grade at Lewis & Clark Junior High School, with my sister, Susan away at Oregon State University. I was outside during PE class when someone came from the office to get me because Mom wanted to talk to me on the phone. Bobby had called the night before and told me that he would fly into Yakima the next day, on his way to deliver a Cessna to Seattle. But Bobby hadn't called, and Mom was trying to make sure that I had gotten the message right. I walked home and the waiting began for word of Bobby, with a search under way along his planned flight route. We waited for three days, the longest three days of my lifetime, while we prayed that he might be found safe. Family and friends would come to the door to bring food and spend some time with us while we waited for news. The third day there was another knock, and we found two policemen standing at the door. They brought the news that Bobby's plane had been found been found. It had crashed into a mountain in southern Idaho, and Bobby was dead.

Dad had lived a full life before his plane crash in Alaska, and his death was hard yet could eventually be accepted. But Bobby was just emerging from his youth and starting to find his way in the world, with so much promise ahead, and his loss brought unfathomable sadness. It was surely the hardest blow that Mom ever took in her life, from which it took many years for her to recover. I can tell you this much with certainty: you do not want to outlive your children.

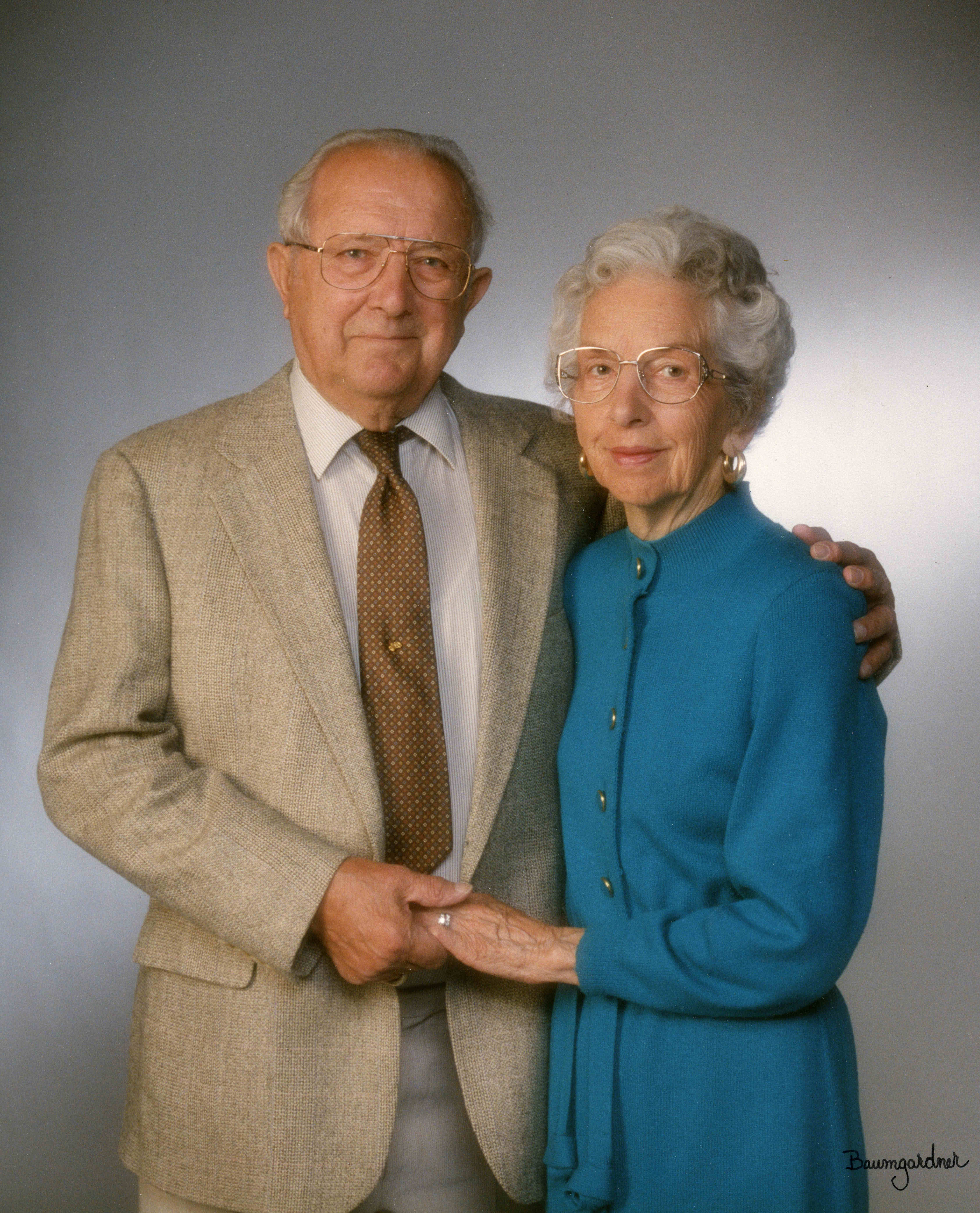

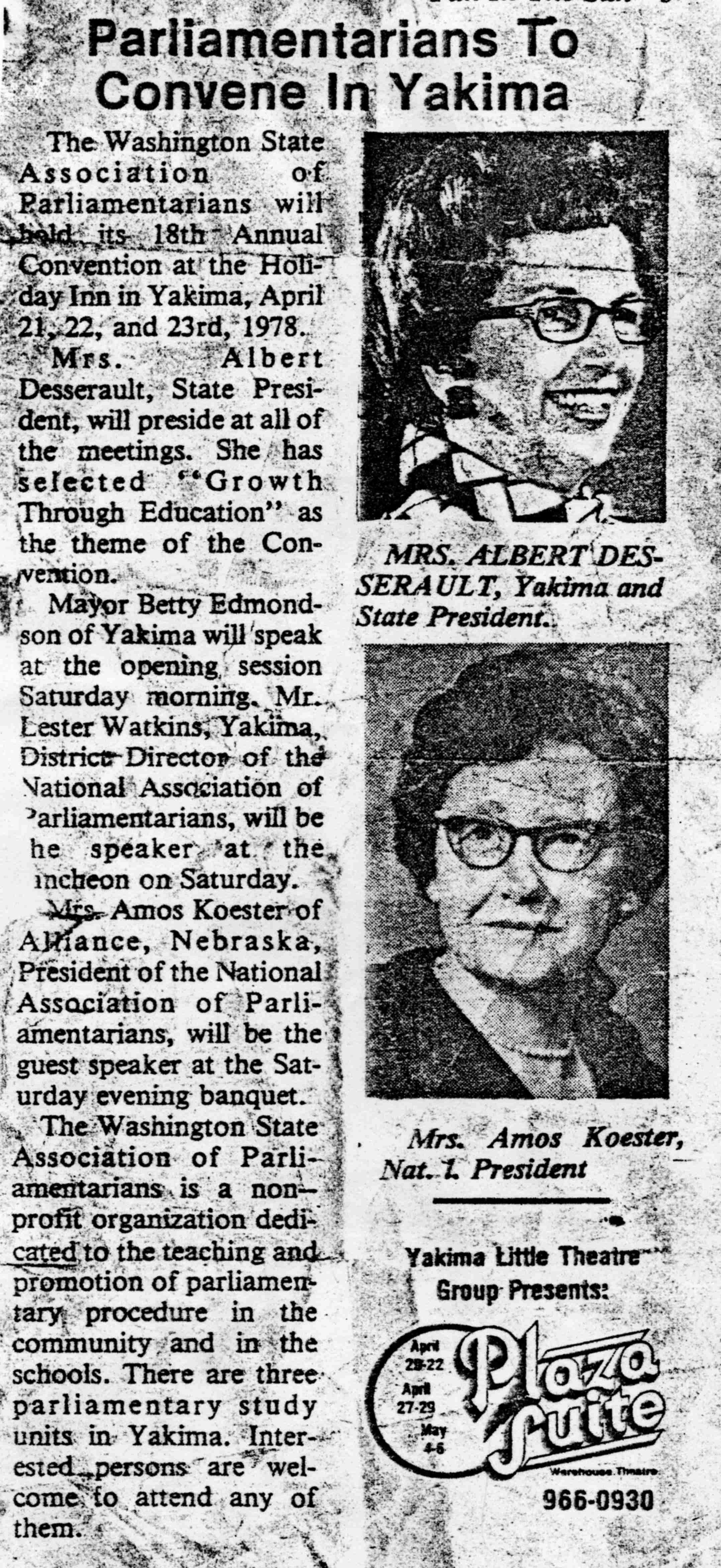

When I was a junior in high school, with Susan through college and married, Mom was still working hard to make ends meet. Then a wonderful thing happened: through a friend of hers, Mom met a man named Albert Desserault, who was a farmer from Moxee, a small town about ten miles east of Yakima. It was love at first sight. I remember Mom being upbeat and cheerful, and then nervous when Al came to the house to meet me for the first time. Kind of weird at that age to watch your own mom fall in love, but also really wonderful given that I was soon to leave the nest, after which she would have been all alone. It didn't take long Mom and Al to decide to tie the knot. The wedding was in Hawaii, where Susan's husband, Bill was flying P-3 antisubmarine warfare planes and was stationed at Barber's Point Naval Air Station. Mom was radiant, Al was beaming, it was the first time in Hawaii for all of us, and just the neatest thing for both of them, great people that they were.

Meeting Al really brought Mom back life after the terrible blow of Bobby's death. And it was much the same for Al, who had lost his twelve-year-old son Larry to a tractor accident on the farm, then lost his first wife, Leona to a heart attack less than a year later. With all of his three older children either married or in college, the happy farm family life that Al's had cherished suddenly vanished before his eyes. Mom and Al were just what one-another needed.

For the first time Mom didn't have to work long hours to pay the bills. But instead of slowing down and relaxing, she turned her energy to her other interests and public service. She had joined a Toastmistress club in order to develop the public speaking skills that she needed to teach sewing lessons, so she increased her level of involvement. She also took interest in parliamentary law, the rules by which public organizations draft their bylaws and conduct their meetings. She joined a parliamentary law club, became an expert in Roberts Rules, served as the parliamentarian at many meetings including the Washington State Bowler's convention, and then started two new parliamentary units. One of them took her name and became the Agnes Desserault Parliamentary Law Club.

With Al came a big, wonderful family for Mom to enjoy. Al had three children: Ken, Eileen, and Jan. Al had a twin brother Bob, also a farmer in the lower valley, and three sisters. As Al turned over responsibility for the ranch in Moxee to son Ken, there was plenty of time for family get-togethers and for Mom and Al to take long trips in their big, comfortable camper. They spent many happy years together while living at 607 South 27th Avenue in Yakima. During that period Susan and I often brought our kids over to be with them, especially in the spring at big Easter family gatherings.